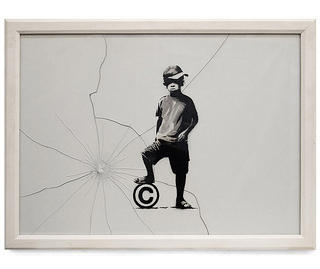

I haven’t written much here about my dissertation research, but occasionally there’s a story that expresses well the point I’m attempting to make — law doesn’t work well when it’s misaligned with social norms.

I haven’t written much here about my dissertation research, but occasionally there’s a story that expresses well the point I’m attempting to make — law doesn’t work well when it’s misaligned with social norms.

Internet Service Providers (ISPs) have just revealed their new strategy for working with the content industries to crack down on internet piracy (How ISPs will do “six strikes”: Throttled speeds, blocked sites | Ars Technica). The approach takes 3 phases: notice, acknowledgement, and punishment. A spokesperson said that the goal was not to stop heavy-downloading “serial pirates.”

[ISPs goal is to] educate “the vast majority of the people for whom trading in copyrighted material has become a social norm.”

The 3 steps certainly have a better chance of success than the bland, generic copyright “education” of the past, but still might fall short for achieving the kind of change content owners are looking for.

My research is starting to reveal that norms usually trump law, despite “education” efforts. Media effects and psychological theories point to difficulty of overcoming factors like our natural tendency to think heuristically and the power of group norms. I’m sure these measures will bring a small decrease in downloading, but I predict a push-back as our culture engages in more online creativity. Especially if that creativity is an individual’s livelihood!

I’d argue that there are also issues of private enforcement of law here, but that is an issue for another day.